In which my recent reading of Bob Dylan in America by Sean Wilentz and listening to the new release of Dylan’s 1962-64 Witmark Demos provoke further reflections on an American bard.

I’ve been listening to Bob Dylan since the night I first heard his voice in 1962. It didn’t sound like any voice I'd ever heard and it just about knocked me to the ground with its raw and undefended power. I was 17, a high school senior living in the small Southern California resort town, Palm Springs, where I knew no one who shared my passion for the folk music that was being “revived” in big cities across the country.

I’d learned to play guitar during summers spent at an arts camp in the nearby San Jacinto Mountains where kids and adults could study visual arts, music, dance and theatre. It was certainly ahead of its time: a cultural oasis and one of the few places that would hire blacklisted artists like Pete Seeger. He ran a two-week long folk music workshop there every summer from 1956 until sometime in the 1960s. At fourteen I started learning a little blues guitar from Texas legend, Brownie McGee, who, with the equally legendary harmonica player Sonny Terry, taught at the folk music workshop for several years. During the nine months of the year, back in Palm Springs, I had to make do with Folkways LPs of Pete, Brownie and Sonny and other newly re-discovered bluesmen and women from Texas, the Mississippi Delta, and other mysterious places.

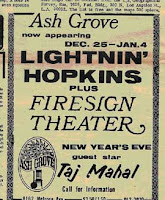

I’d learned to play guitar during summers spent at an arts camp in the nearby San Jacinto Mountains where kids and adults could study visual arts, music, dance and theatre. It was certainly ahead of its time: a cultural oasis and one of the few places that would hire blacklisted artists like Pete Seeger. He ran a two-week long folk music workshop there every summer from 1956 until sometime in the 1960s. At fourteen I started learning a little blues guitar from Texas legend, Brownie McGee, who, with the equally legendary harmonica player Sonny Terry, taught at the folk music workshop for several years. During the nine months of the year, back in Palm Springs, I had to make do with Folkways LPs of Pete, Brownie and Sonny and other newly re-discovered bluesmen and women from Texas, the Mississippi Delta, and other mysterious places. I also spent every weekend I could at my aunt’s house in L.A, a three-hour Greyhound Bus ride from the desert. In LA, I had friends from the camp who also played guitar and listened to the same music that I did. I had an uncle, the black sheep variety, who smoked and drank and would take me to the only folk club in L.A. at the time, the Ash Grove, where we might hear Lightnin’ Hopkins or Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, or someone wonderful I’d never heard of. My uncle would let me drink beer and smoke cigarettes while he told stories about being a young radical in Chicago during the depression.

On those L.A. nights when neither friends nor uncle were available, I stayed home at my aunt’s (my uncle’s older sister), happy to play records on her hi fi. Moreover, at 11 o’clock on Saturday nights, an FM DJ named Les Claypool Jr. played folk music into the wee hours. His show was a mix of Folkways archives, fifties headliners like Pete, The Weavers and Josh White, and a few of the emerging "folk" singers like Joan Baez, Judy Collins, and Tom Rush, but nothing as commercial as the Kingston Trio or the Brothers Four. I loved almost everything he played and would record his shows on a reel-to-reel Wollensack monaural tape recorder. That night, Claypool said something in a sceptical tone about the cut he was about to play from a debut album by an young unknown from the East Coast with a pretentious pseudonym, but I wasn’t paying too much attention. Then I heard that voice I’ve come to know in a way I know very few others sing: “Well, there’s one kind-uh favor I’ll ask a you....” And everything changed. Can you imagine the pure strangeness of that moment?

I couldn’t picture the singer. Young? Old? Black? White? If it hadn’t been for the absence of scratches, hisses and pops, I could almost have imagined he was an obscure bluesman from an archival field recording by one of the Lomaxes. The weathered sounding voice rang with vitality. It took pleasure in itself. That was – in those days – unusual. Cool was still cool. Most white folksingers still accepted the performance conventions of traditional folk balladry and were pretty dead-pan, even stone faced. Musical performance west of Broadway was a pretty contained affair. When Elvis moved his lower body on national TV for the first time, it was treated as a full blown explosion of uncontrollable Dionysian sexual madness that had to be immediately contained. The cameras were instructed to never tilt down below his belt buckle. Handlers and guards were brought in to attend to the screaming and fainting adolescent girls.

I’d heard the traditional, if irregular, blues “See That my Grave is Kept Clean” on a Folkways re-release of the original Blind Lemon Jefferson field recording, which is actually more mellow and contained than Dylan’s version. What I heard that night was sung at a pushed-up pulse driven by a relentless guitar groove in drop D tuning (that’s when the low E string is tuned down a whole-step to a deep, ringing D). I heard a voice that confounded all the categories I’d learned that were supposed to make “good,” "pleasing,” “beautiful” sounds. The voice was singing with such apparent vigor about all that frightened me the most: graves and coffins, death come too soon, white horses as ghostly omens. I was shaken by the contradiction.

Nearly fifty years later, I’ve been reflecting a lot on Bob Dylan. One of the reasons for this is the recent publication of Sean Wilentz’ magisterial study, Bob Dylan in America along with the release of Dylan’s remastered demo tapes that he recorded on the fly between 1962 and 1964 when he was writing songs faster than he could make records. In the liner notes to the Witmark Demos, we learn that executive Artie Mogull would let Dylan lay down demos in his office anytime he wanted. In a process that had changed very little for a century, the low quality tapes would be hand-transcribed into proper musical notation by a music copyist and a one-of-a-kind acetate disk would be made from the tape. The disk and a copy of the lyrics and music would then be sent to any singer that Mogull felt might be interested in recording the song. The list of unlikely pop stars who recorded covers of early Dylan songs is worth its own study. Dylan’s first album, the one that I can still listen to endlessly, was a flop when released, selling around 5,000 units. But before he recorded his second album, a hot new folk-pop trio, with a very lovely blond singer and two cool guitar players with neatly trimmed goatees recorded one of Dylan’s first original songs, Blowin’ in the Wind. Yep, Peter, Paul and Mary, packaged by the legendary Albert Grossman who also managed Dylan. The immense success of that record launched Dylan into a rocketing trajectory of growing celebrity that didn't slow down until he hit the inevitable set-backs and retrenchments of his mid-career years.

As I listened to the forty-two tracks on the Witmark Demos, some sounding as if they were being sung and played through for the first time, I was deeply moved by the enormous range of material this twenty-two year old had taken into himself. You can hear so many tributaries of wild American poetry, history and song coursing through his voice, through his fingers on the guitar, through his breath pushing into his mouth-harp, through the sounds, the vowels and consonants he shapes with both care and abandon and, always, deep generosity.

As I listened to the forty-two tracks on the Witmark Demos, some sounding as if they were being sung and played through for the first time, I was deeply moved by the enormous range of material this twenty-two year old had taken into himself. You can hear so many tributaries of wild American poetry, history and song coursing through his voice, through his fingers on the guitar, through his breath pushing into his mouth-harp, through the sounds, the vowels and consonants he shapes with both care and abandon and, always, deep generosity.Reading Wilentz as I was coming to the end of my first listen-through of the Demos was like continuing a conversation I hadn’t realized I’d begun. Though Wilentz is a fully-credentialed big-time academic – a professor of American History at Princeton and author of several major tomes on the origins of American Democracy – his writing is passionate, conversational, erudite and down-to-earth.

He reveals rather than manufactures connections between Dylan and his cultural, spiritual, musical and philosophical ancestors who include so many more than the obvious ones we expect to find. This doesn’t diminish the importance of Dylan's love for Woody Guthrie or the extent to which he modelled much of his early work on Woody’s. But I had no idea, for example, that Aaron Copland was as important an influence on Dylan as Wilentz suggests.

Wilentz does no less than locate Dylan in an American cultural landscape that is darker, stranger and more inclusive than the sanitized, conventional version. In Dylan's America, which I have no trouble recognizing, there's a figure-ground reversal going on. The marginalized are now at the center. The ones to watch and listen to are the dissenters, the prophets and the rebels in their various changing forms as poets, reformers, preachers, minstrels, vagabonds or outlaws. Wilentz shows us how the founding fathers, and Civil War poets, how Ovid, Dante, the Bible, Milton, Blake, Whitman, Poe, Aaron Copland, Roy Rogers, Brecht, Kurt Weill, Bessie Smith, Kerouac, Ginsberg, Corso, Da Vinci, Ferlinghetti, Guthrie, Leadbelly, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Frank Sinatra, Blind Willie McTell, Bing Crosby, Mother Mabelle Carter, Charlie Chaplin, the Sacred Harp, Robert Johnson, Sholem Alechem all appear in Dylan's America, often masked and anonymous, paraphrased, disguised, or transformed, but always honored.

In this version of American culture, there’s no attempt to cover up the raw racial wounding that remains unhealed since the times of slavery. I wonder if what I first heard in Bob Dylan’s voice in 1962 was a preview of his approaching immersion in the American shadow, which sometimes seems to be an elemental curse coming from the nation's origins in theft and violence. Today I listened to the 1967 release, John Wesley Harding, for the first time in at least a decade. Though the songs on this album have always moved me more deeply than many of his others, I had never felt the particular mixture of anger and grief in them as I did this time. They had a weight to them that went beyond the personal.

Listen to this deceptively romantic waltz:

I pity the poor immigrant

Who wishes he would’ve stayed home

Who uses all his power to do evil

But in the end is always left so alone

That man whom with his fingers cheats

And who lies with ev’ry breath

Who passionately hates his life

And likewise, fears his death

Who uses all his power to do evil

But in the end is always left so alone

That man whom with his fingers cheats

And who lies with ev’ry breath

Who passionately hates his life

And likewise, fears his death

[...]

I pity the poor immigrant

Who tramples through the mud

Who fills his mouth with laughing

And who builds his town with blood

Who tramples through the mud

Who fills his mouth with laughing

And who builds his town with blood

And, the last verse of a lyric that Dylan set to melody and form of the old labor ballad, I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill:

I dreamed I saw St. Augustine Alive with fiery breath

And I dreamed I was amongst the ones

That put him out to death

Oh, I awoke in anger

So alone and terrified

I put my fingers against the glass

And bowed my head and cried

When I listen to these and so many of Dylan's other songs today, I hear American grief, rage and frustrated love howling through the bones of our history.

And I dreamed I was amongst the ones

That put him out to death

Oh, I awoke in anger

So alone and terrified

I put my fingers against the glass

And bowed my head and cried

When I listen to these and so many of Dylan's other songs today, I hear American grief, rage and frustrated love howling through the bones of our history.

photos: from top: Sam "Lightnin'" Hopkins, Ash Grove flyer, 1964, both from Ash Grove, Music Foundation Web Site.

I would love to hear more about how this Dylan insight ties into what you e-mailed out earlier today on the current unemployment/economic/political situation. It seems that somehow Dylan is speaking to this time as well.

ReplyDelete